A Ghost Story

When an acquaintance recounted the following story, she warned that some details might be disturbing. I’ll leave that for you to decide.

THIS FOLLOWING RECOUNTING IS BASED ON A TRUE STORY

Originally published January 2021 on nicolejeffords.com

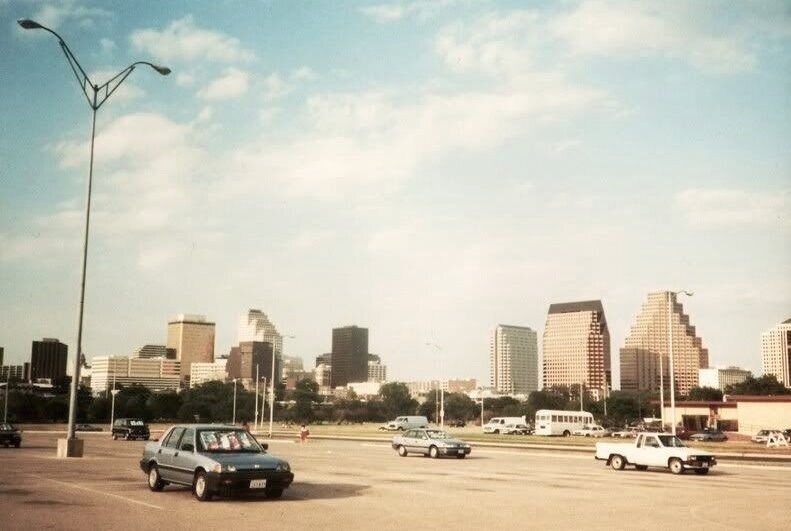

1980’s Austin/ Image: r/Austin

The etiquette around death and dying is often a messy business. I was recently told the following story by an acquaintance, a woman named Lydia Rose who runs an art gallery/frame store not far from where I live in North Austin. Since I’m a person always seeking out odd details in other people’s lives, I will tell you that I’ve heard that Lydia once worked as a stripper in a sex club somewhere in South Austin. (This would have been quite a number of years ago; the Lydia I know now is middle-aged and definitely dumpy.) There’s also a rumor that Lydia got kicked out of her house by a bad boyfriend and ended up, for a while, on the streets. But all of that is conjecture. When Lydia recounted the story, she warned that some details might be disturbing. I’ll leave that for you to decide.

Lydia was originally from someplace else -- a small town in upstate New York -- and traveled to Austin in the mid-eighties, when she was about twenty years old, to surround herself with music and eventually complete her education. She worked as a pole dancer and stripper in those early years in order to pay tuition costs at UT. It’s hard to imagine this since she’s not particularly sexy-looking, a small woman with short curly brown hair and an intellectual face, who, to this day, goes around like a student in jeans and oversized shirts and sweaters. She may have been married once or twice, but has no children and lives by herself in an apartment complex off Jollyville Road. The story she told me began five years ago, in 2015, when she was leaving a party and called an Uber.

The problem is she had no memory of the party, or the Uber ride, because she was drunk. She got sick and puked all over the car, then passed out.

The driver had to half drag, half carry her from his Toyota Camry to her apartment, but then she couldn’t find her key and wasn’t even sure if this was the right apartment, and a neighbor who claimed he’d never seen her before yelled out the window for her to shut up and stop wailing, so the poor driver had to drag her back to his stinky car and figure out what to do. He probably wished he could just dump her at the curb, but he wasn’t that sort of man. Instead, because he had no other options, he signed out of Uber and drove her back to his place.

The next morning, Lydia woke in a strange bed with an unknown man leaning over her. His name, he told her, was Danny Lieber, and he worked both as a therapist and as an uber driver. He was perhaps ten years older than she was, sixty-ish, and he was extremely unattractive -- not ugly, Lydia thought as he handed her a cup of coffee, but not handsome either, with a bulbous nose, pockmarked skin, and a head of wild, bushy, graying hair. She registered his looks first, then noticed his warm smile and the incredible kindness in his eyes.

“About last night,” he said.

She groaned. “I’m not sure I want to hear about it.”

“Well, you’ll owe me money to have my car detailed.”

Lydia hid her face in her hands. “I guess I made a complete fool out of myself.” She opened an eye and squinted at him. “How did I even get here?”

That was the beginning of their singular friendship.

Sketch by Nicole Jeffords

For the next four years, Lydia and Danny saw each other at least once a week, spoke on the phone every night, texted frequently throughout the day. They weren’t lovers -- neither had that kind of interest in the other -- but they were close, if not best, friends. What Lydia learned, almost from the outset, was that Danny was funny. His one-liners and witty sense of humor could have landed him spots in comedy clubs, but that wasn’t his thing; he was just a naturally funny guy, and people thought of him that way -- as a bit of an entertainer. As a result, he had lots of friends and admirers, though his popularity never translated into much of anything in the girlfriend department. He’d had one marriage that ended in divorce after producing a son and daughter, and that was it. For Lydia, an only child, he was the closest thing she’d ever had to a brother.

And then he got sick. He wasn’t a cigarette smoker, but he’d been coughing a lot, serious fits that racked his whole body, and his doctors diagnosed exactly what he most feared: lung cancer. In the beginning, the prognosis was hopeful (the doctors gave him a good 2-3 years, if not more), and he learned to live with the disease, going to parties, driving Uber, working with clients as he’d always done, even though the chemo made him extremely tired. But then, at the end of his first year, things went south, and suddenly he had six weeks to live. Lydia began to stop by his apartment every day.

Although she knew other people visited, she never saw anyone else when she was there. Hospice nurses and caregivers stopped by in the morning, and Danny’s daughter, Jennifer, whom Lydia had never met, kept the fridge filled with juices and take-out. Lydia’s job, as she saw it, was to keep Danny entertained, get him anything he needed and tidy up.

Danny told Lydia that he wanted a joyous death. He asked her to video him expounding on his life and all the things he’d learned, but mostly he talked about the fact that he was a devout atheist and love was all that mattered.

By the second day of filming, his thoughts, which had been cogent the day before, wandered too much to make sense. Lydia, living deeply in the moment, realized that this process of dying was going to be quicker than she’d anticipated. There wouldn’t be a wealth of time, as she’d hoped, but rather a swift decline, with rapidly occurring cognitive changes that, whether due to illness or drugs, would take Danny to a place where she could no longer communicate with him. Holding back tears, she’d tuck him in under his blanket and bring him glasses of water. One afternoon, looking for hand lotion, she discovered a rolled up sock containing a wad of cash in his night table drawer. “Jesus, Danny, what’s this doing here?” she said.

Turned out it was a considerable amount of money, eighteen thousand dollars, his life savings. “Put it back in the drawer,” Danny ordered.

Lydia told him that wasn’t safe, the drawer was too obvious a place with all the different health care workers coming in and out of the apartment. After some deliberation, she pushed the sock deeply into a sneaker in a shoebag in the closet. “This is where I’ve hidden it,” she told Danny, who nodded as if he understood what she was saying.

But he didn’t, brain too foggy from drugs. And there was hell to pay.

“I don’t know, I don’t know,” wailed Danny.

“The caregiver was here this morning. I’ll bet she took it,” said Jennifer.

“No, actually it was me,” Lydia announced quietly.

Jennifer turned to look at her, incredulity on her face. “You took it?”

Lydia nodded. “The night table was too obvious a place, so I moved it to a sneaker in the closet.”

“Well, how the hell was I supposed to know that? You have my number, you could have called me instead of putting us through all this anxiety. Things are bad enough as it is.”

Lydia apologized. Then she said, “The money in that sock should go to the bank.”

“Yes, but it makes my father happy to have it by his bed where he can keep an eye on it.” She reached down and gently patted Danny’s shoulder. “Right, dad?”

But Danny had no idea what they were talking about. His eyes were glazed and his cadaverously thin face blended into the white sheet that covered the chair. Drool leaked from his mouth as he said, “You think they’ll let me drive Uber in heaven?”

Wow, thought Lydia. So much for her friend’s staunch atheism. She tried to fight back despair, not knowing if it was the drugs causing Danny to talk about heaven, a place he’d never believed in, or if he was getting that much closer to death and celestial thoughts were entering his head.

“Anyway,” said Jennifer, “I don’t want you moving things around here ever again. You’re very nice coming in to see my dad like you do, but that doesn’t mean you get to make decisions.”

If Lydia was stung by those words, she didn’t show it. Danny was like a brother and she would visit him every single day to the bitter end if she had to.

The next afternoon both Jennifer and her husband, Jim, were at the apartment when Lydia arrived. “We have something to tell you,” Jennifer said, looking a little embarrassed. “Jim booked a trip to Canada months ago, before dad got so sick. Everything’s prepaid, so we have to go. In the meanwhile, we’ve decided to move dad to a nursing home. We want to know he’s well-cared for.”

“He can be well-cared for here at home with his things all around him,” cried Lydia. “A move like that could kill him.”

Jennifer gave her a sadly resigned look. “We’ve made our decision,” she said. “And that’s that.”

Lydia didn’t understand how Jennifer could take off on vacation while her father, Danny, was literally at death’s door. And stick him in a nursing home! What normal person would do that?

She figured that Danny himself had insisted, while he was still lucid, that it was fine for his daughter to travel even though he was so sick. “You guys go off and enjoy yourselves,” he would have said. “Nothing’s gonna happen. I’ll be okay. I don’t want you to cancel a prepaid vacation because of me.”

And now here he was in a brand new nursing home that was out of the way, difficult to get to. His room was at the end of a long, wide, empty corridor. To Lydia, the place was so quiet it seemed as if no one was there. She found Danny scrunched in a fetal position, looking as tiny and transparent as the wing of a moth. He was no longer able to talk. She sat with him a long time, just studying the tightly closed eyes, the gaping mouth. That was on Saturday the twenty-seventh of July. Two days later he was dead.

In the two days before he died, Lydia encountered no visitors in Danny’s room. She knew his son lived in Washington state, but never saw him. Where were all of Danny’s friends? It made her sick to see him dying alone. The nurses told her Jennifer called every few hours from Canada. They also told her Jennifer had said her father was too far gone for social visits, just to let him rest.

Bullshit, thought Lydia. She didn’t want to get mixed up in family business, but there was maybe one small thing she could do to make the situation right. Outside it was hot and sunny. For Lydia the day was black. When she arrived home that night, she got on Facebook. She wasn’t supposed to put anything about Danny online, but the hell with that -- she posted the following:

Danny Lieber, beloved by so many and seriously ill, is spending his last days at Legend Oaks Healthcare, and could use visitors.

The next night, the last for Danny on earth, Lydia drove to the nursing home straight from work. Danny seemed to have shrunk even more, if that were possible. His breathing was raspy and sporadic, despite the nasal cannula providing oxygen. He looked like the shriveled carcass of an insect, not a happy thought.

Lydia sat down by his bed. She put her hand over his, thinking she should sing to him though she had a terrible voice. As she started the first line of Goodnight Moonshine, by Molly Venter, a woman walked in with a guitar which she unloaded from its case and began strumming gently. Five minutes later a man entered with two small drums. Then a woman with a flute. Pretty soon there were six people around his bed, then seven, then eight, all of them singing. The music didn’t necessarily bring joy to Danny’s face, but it did bring a feeling of solemnity and awe to the room. More people arrived. Now there were ten, now thirteen, now twenty. All sat or stood around Danny’s bed, swaying together, reaching down to pat his arm and face and hands. It felt as if they were in a very sacred space, about to witness a miracle.

And then, shortly before midnight, the miracle occurred. Lydia saw it with her very own eyes. Danny’s body had become translucent.

He lay still and peaceful until suddenly, with a frantic movement, he attempted to raise his arms as if beckoning to someone. His mouth opened and closed, but no words came out, just a strangled cough. And then, as everyone in the room watched, a ray of light that was visible under his skin traveled from Danny’s heart to his throat and out the top of his head -- a bright white incandescent ray that circled close to the ceiling three times, dimmed and brightened purposefully, and faded away.

“Goodbye, Danny,” whispered Lydia. She didn’t know where the light was going, but she knew what it was, and she felt privileged to have seen it. Perhaps, she thought, some of it had entered her own body to remain treasured there forever. For a few days she felt oddly light and buoyant. But it wasn’t till Jennifer returned home and contacted her that she learned more about the light and where it had really gone.

***

Danny’s daughter, Jennifer, felt… well, there are no words for what she felt, taking off for Canada while her father was dying.

She was a slender woman in her mid-forties with eggplant-colored hair that hung in a scraggly braid past the bra line. She always wore her hair that way, mostly for convenience, and people assumed she was a hippie, which made sense because she also always wore Berks or other ugly, heavy-looking health shoes. And that made sense too, since, by profession, she was a pedorthist and had worked in the comfort shoe business for years. Her husband, Jim, was a popular orthodontist in town, a sweet, mild-mannered, pudgy man who occasionally threw fits of petulance if things didn’t go his way. This was one of those times.

Although Jim was not much of an outdoors man, the idea of a week fishing at an exclusive resort in Ontario was thrilling to him. He was tired. He spent long days fitting metal wires to crooked teenage teeth and badly needed a break. The previous summer they’d gone to Europe, but this year Jim decided total rest was required and booked them into a fish camp in French River, a four hour drive from Toronto.

Neither he nor Jennifer knew what a fish camp was exactly, but when Jennifer announced she couldn’t go anywhere with her father so close to dying, Jim dug his heels in and said they’d paid for a twenty thousand dollar vacation and they had to go no matter what.

“But he could die while we’re gone!” cried Jennifer.

“He won’t. And besides, he told us to go. He wants us to be happy! We’ll keep in touch with him the whole time, and it’ll all work out, you’ll see.”

He was right that Danny had pleaded with them to go on their trip, but Jennifer was extremely uneasy about it and dreaded leaving her father in a nursing home, even though they’d been assured he’d receive excellent care. Her husband, she thought, was a selfish fool. But in the end it seemed too complicated not to go along with him. With a wilting heart, she flew with Jim to Canada, spent a night in Toronto, and then drove north, a whole day’s trip through miles and miles of barren uninteresting territory till they reached the end of the road. Literally. They were looking at a small body of water, a rough beach, six or seven cabins, and a sprawling wooden lodge.

On the other side of the lake loomed a dark line of trees, an endless forest, the tallest pines Jennifer had ever seen. Beyond the fish camp clearing there were trees, too, and Jennifer realized they were in the middle of nowhere, true wilderness, and itched to put on her new Merrell hiking boots and dive into the woods where she was sure, for a time, she’d find the peace and courage she needed before going back to her dying father.

The cabin they were assigned to was secluded and comfortable. Being in a strange place, fifteen hundred miles or so from Austin, made Jennifer feel -- falsely -- as if things were actually okay. She had never been in a place as remote as this. On their first morning, she went straight to the reception desk to ask for a map of the hiking trails. All they had was a flimsy piece of paper with lines penciled in showing three or four trails looping from the fish camp into the vast expanse of woods and back again. “Where’s the entrance?” she asked. The young man at the desk explained in some detail how to get there, but when Jennifer and Jim went looking later that afternoon they had trouble finding the trailhead. They searched for about fifteen minutes and when they eventually found an unmarked entrance hardly noticeable in a line of trees edging a parking lot beyond the last cabin, they slapped hands and into the woods they went.

It was about three-thirty. They only intended to go a little ways and come back for a real hike the following day. But the moment they entered the woods they were so enthralled by the terrain that they couldn’t stop walking. It was as if they had gone, in a split second, from one world to another -- the fish camp with its open views over the lake to a cloistered wall of trees, hundreds and hundreds of trees. Since they hadn’t planned to be in the woods for long, they’d brought very little with them, just their phones and a bottle of water. Neither of them talked, but there was an unspoken agreement between them that this short hike was delicious and they had to keep going for a while. Ten minutes tops. The trail was rudimentarily marked with small red flags; they were aware of two or three paths leading off from it, but figured if they stayed on the original trail, they’d be fine.

And for a while they were. The woods were so captivatingly beautiful and the trail felt so good beneath their feet that they kept going and going. Ten minutes became fifteen and then twenty and then half an hour.

Both had forsaken watches on vacation, but when they looked to see what time it was, they realized their phones had stopped working -- no signal this deep in the forest.

There was still plenty of daylight, but the sun was beginning to slant westward and its rays were drifting less and less strongly through the tops of the trees. Jennifer figured they had been on the trail for about an hour now. The flags marking the way had grown intermittent. They passed a beautiful little lagoon and she wondered if it was the same she’d seen five minutes ago or a new one. And then she realized that everything -- every tree and rock and brief clearing in these woods -- looked identically the same and they had no idea where they were. They hadn’t seen another human the whole time they’d been out here.

The little red flags marking the trail had disappeared. Jennifer’s stomach lurched and felt like it was going to plunge between her knees as she admitted to herself they were lost. “Let’s just turn around and go back the way we came,” said Jim.

But when they turned around, they saw the way wasn’t clear. There were several vague, unmarked paths leading in different directions, and they weren’t sure which to take. A few yards ahead lay a rocky clearing and Jennifer ran to it, thinking she might get a view of the fish camp lodge in the distance. But when she reached the clearing, all she saw was miles and miles of wilderness, the same terrain repeated over and over again with not a single sign of human habitation. To make matters worse, the light was beginning to fail. Not that the sun had left the sky, but rather that its rays could no longer penetrate through the tops of the pines to the floor of the forest. “It’s going to be okay,” murmured Jim in a nervous voice. “The important thing is not to panic.”

Doggedly they continued, not knowing if they were looping back to the lodge or heading deeper and deeper into the woods. The path was rough and uneven and required total concentration; one wrong step and an ankle would twist or break. By now they’d drunk most of their water. Both of them were in shorts and T-shirts and it was growing cooler. Jennifer was annoyed that Jim had worn sneakers instead of a good pair of hiking boots, as she had advised before they left their cabin. Her own feet felt cushioned and secure in their Merrells, but ahead of her she could see Jim was tiring and his steps were wobbly negotiating the roots and pebbles of the path. And then he fell. He gave a sharp yelp as he crashed to the ground and sat there, looking stunned and miserable, clutching his ankle which immediately began to swell. “Oh fuck!” cried Jennifer. “Fuck, fuck, fuck.”

She tried to keep herself calm as she examined his ankle, running fingers over the swollen flesh, but she knew the game was over: Jim had a bad sprain -- or even possibly a break -- and was no longer able to walk.

And she, a thin delicate woman, would not be able to drag him with her as she tried to find the way out of the forest.

“You’ll have to go ahead without me,” moaned Jim.

Both his knees were badly scraped and Jennifer’s mind immediately went to the possibility of infection -- if she’d known they were going on this long a hike, she’d have brought backpacks filled with Neosporin, aluminum blankets, flashlights, trail mix, water, a compass, matches and a sharp knife. But they had nothing. And now the light was really growing dimmer.

“Don’t worry about me,” said Jim. “Go now while you have a chance, and be sure to mark the path so the people at the lodge can find me when they come back in their ATVs.”

“I think I should stay with you, Jim. It’s going to be dark soon. We can tough it out tonight and then tomorrow morning I could get a fresh start.”

“No!” cried Jim. “You’ve got to go now and bring back help. Don’t worry about me. Just go!”

And so, against her own best instincts, Jennifer took off in the darkening woods, not knowing which way would lead back to the lodge and salvation.

It didn’t take long before she realized she’d made a colossal mistake. She should have stayed with Jim, tried to move logs and branches around to build some sort of shelter. Surely, once the staff at the lodge became aware they were missing, someone would be sent out to find them. She didn’t have matches, but she could have rubbed two sticks together to start a fire, and then not only would she and Jim have been kept warm, but the smoke might have drawn attention.

But she hadn’t done that. In a panic, she had sprinted off, and now she was even more lost than ever.

She contemplated backtracking to find Jim, turning around to head in the direction she’d come from, loudly calling his name. And that’s what she did -- but there was no response, just stillness, silence, the forest’s vast indifference. She sat down on a rock for a moment to assess her situation. It occurred to her that the wilderness, gorgeous as it was with its crystal clear lagoons and endless legion of trees, was also brutal in its total indifference to humans. This was nature at its finest, but it didn’t give a shit about her. With that thought, she stood up wearily and continued walking. And walking and walking.

The further she went, the more things looked alike.

It was getting cold, and twilight was fast descending on the forest. Jennifer was suddenly so thirsty she couldn’t stand it. Fear began to eat at her like a dangerous animal taking big bites. What if she died in these woods? What if her children, who were now in summer camp, never saw her or their father again? And what if her own father, stuck in a nursing home that might be as indifferent to him as this forest was to her, drew his last breath without her ever saying goodbye?

At the thought of her father, tears brimmed in Jennifer’s eyes and she started sobbing. The forest was silent around her. She tried to gain control of herself, bending to peel some moss from a stone on the ground and using it to wipe at her nose and eyes. Then she continued forward.

She had to keep moving if she wanted to survive. The only problem was, she didn’t know which way was forward, backwards, sideways.

For all she knew, she was going in circles since wherever she went looked like where she’d just been.

And then, almost like an affront, a deeper darkness began to fall. In a few moments she wouldn’t even be able to see her hand in front of her.

And now, the darkness was so total that Jennifer, heart beating wildly, was forced to stop. She couldn’t see the ground well enough to avoid tripping over roots or fallen branches. Without a flashlight she was stuck, the blackness of the forest spreading ominously around her. Too late to build the most rudimentary of shelters, Jennifer got down on her hands and knees and felt for a mossy spot to sit on, thinking she could use handfuls of leaves and pine needles to cover herself.

That didn’t work quite as well as she hoped. She was cold, so cold, her face wet and dirty from being soaked in tears, her whole body shaking. She couldn’t possibly stay here all night! But she had no choice and as she hugged her arms around herself, the true nightmare began. Behind her, suddenly, a creaking sound. Her heart stopped. She forced herself not to scream. What was that? The sound disappeared, replaced by other sounds, some of them very close to her in the dark. She felt something crawl over her leg and then she really did start screaming. It occurred to her that there were wolves and bears in these woods. Probably bats, foxes and moose, too. Anything could attack or kill her. For all she knew, her husband Jim, helpless and wounded, had been eaten alive in the exposed spot where she’d left him.

Gripped by a terror she couldn’t control, her mind went blank -- there was only raw panic. She stood and began to run, branches scratching her cheeks, whipping at her face, but of course she didn’t get more than a few feet before she tripped over something and fell. Wisdom told her to lie where she was, not take any more chances, curl herself into a ball and hope for the best. She squeezed her eyes shut. And then, not far away, she heard a rustling sound and footsteps. “Help!” she screamed with all her might.

No answer. She sat up and peered into the darkness. She could feel that something or someone was there. “Hey! Over here! Help me!” she shouted.

Closeby she heard a cough. “Please!” she screamed. The cough was creepy since she couldn’t see the person. For a moment there was silence, and she waited, holding her breath. What if it was a crazy person with a knife? Sweating profusely, she felt around for a rock, which she gripped tightly in her fist to use as a weapon. She’d never killed anything beyond insects (and once a snake) in her life, but if she had to, she’d kill whatever was out there waiting for her.

She held her hand aloft, fingers curled tightly around the rock. Perhaps a minute went by and she heard the cough again, but this time it was further away. As it retreated, she lowered her arm and sank as deeply as she could into a nest of brambles. She was going to die out here and she knew it. She jammed her eyes shut.

When she opened them, she saw what she could only describe as a hazy beam of light shining down into a patch of woods some twenty yards away from her. What the hell? It wasn’t a flashlight -- the beam was too wide and steady. There was all that blackness and then, like a message, a revelation, the misty ray of light that seemed to emanate from the sky. And that weirdly was slowly progressing toward her, as if she, Jennifer Lieber, bleeding, scratched up, terrified, was its true destination. The light moved to a position right above her head and suddenly everything was illuminated and Jennifer could see the rough bark of the trees, the fallen logs and branches, the small gullies of rocks in her immediate vicinity. She stood, without thinking, craning her neck to see the light, wondering what it was and whether she could trust it to lead her out of the forest.

When the light brushed her face, the skin warmed almost as if she’d received a loving caress.

Jennifer realized this was crazy, but in her desperate state she’d have believed anything; she began to follow the light which reminded her of moonbeams drifting down through the trees to form a path on the forest floor. In a kind of trance, her body surprisingly loose and relaxed, she walked for what seemed like hours, never seeing anyone or hearing anything other than bird calls and the occasional flapping of wings. And suddenly, without warning, she took a step and found herself ejected from the forest – the parking lot and cottages of the fish camp directly in front of her, silent beneath a pale, low, nighttime sky.

Jennifer wanted to go straight to her cottage, lie down beneath a ton of blankets and sleep forever, but she forced herself to run to the lodge where she banged on the door for a long time before anyone answered.

They didn’t find Jim until daylight. Three young men went out on ATVs to comb the forest, and when they came upon Jim he was passed out beneath some trees, covered in bites and murmuring to himself. He’d managed to remove the sneaker from his injured foot, and the skin was incredibly red and swollen, hot to the touch. Once loaded onto an ATV, he was taken back to the lodge and then to a local hospital where he spent a day being treated for exposure, shock, and a badly twisted ankle.

Jennifer was treated for exposure, too. It was two AM when she was delivered from the forest, and she learned that her father had taken his last breath a few minutes before midnight, and that a light had been visible, hovering in the air as he left his body. When she did the math, she realized that Danny had passed a little before one in the morning Canadian time, just about when she began seeing the hazy beam of light that led her out of the forest.

Had magic happened? Was it Danny who had come and saved her? Jim scoffed at the idea, saying the night he’d spent in the woods was the worst night of his life, a traumatic ordeal that would take years to recover from. For Jennifer the experience had been mystical, even thrilling as she went over and over it in her mind -- the danger of falling, breaking a limb, the challenge of keeping steady and balanced in a world where everything looked like everything else and darkness fell so quickly. In retrospect, bizarrely, she had enjoyed every minute of it.

When she compared notes with Lydia, who’d seen the light, the life force, leave Danny’s body and travel from the room, Jennifer had no doubt that it was the same light as the one that had descended from the nighttime sky to form a pathway out of the forest.

“See,” she told Jim. “Now we know for sure that life continues after you take your last breath, that all sorts of mysterious things happen.”

Jim didn’t agree. After the ordeal in the forest, he grew more cautious, driving more slowly, eating better, going to the gym, spending more precious time with his children. For Jennifer, it was the opposite. She felt closer to her father than she ever had in life, and experienced a recklessness, a wild abandon, a freedom that made her want to run the empty streets at night, buy a gun and teach herself to shoot, travel to the jungles of Brazil to take hallucinogenic drugs that would show her the way forward. She cut off her braid and allowed her hair to curl loosely around her head. While Jim took up bridge, Jennifer, age forty-six, decided to explore shamanism -- perhaps she herself possessed the witchy, other-worldly traits necessary to communicate with the beyond? Eventually Jim fell in love with one of his bridge partners, and the marriage dissolved. Jennifer had a feeling her father would be happy about that. She bought a house with huge windows overlooking the greenbelt where she could constantly watch the changing patterns of shadow and light moving across the landscape. She wasn’t sure if she would ever marry again, or if that mattered. From her night in the forest -- the night of her father’s death -- she had grown into a larger person, a woman with questions that it would take a whole lifetime to answer.